Exercise-induced cramps -

This tallies with our experience at Precision Hydration. We recently conducted a survey of athletes who had reported suffering from muscle cramps at one time or another. This is especially true for staunch supporters of the neuromuscular theory detailed below.

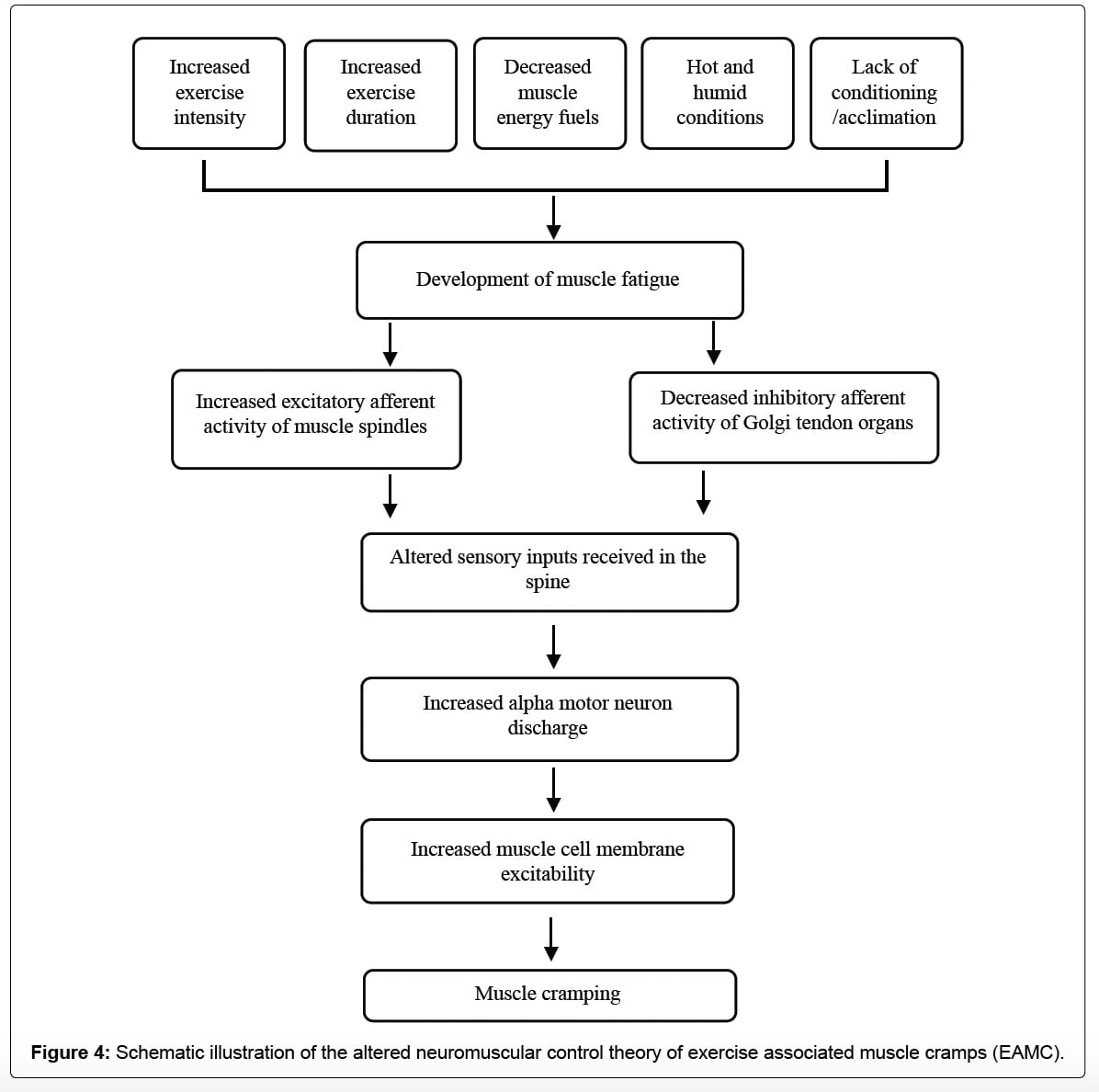

This theory is more recent and proposes that muscle overload and neuromuscular fatigue are the root causes of EAMC. The hypothesis is that fatigue contributes to an imbalance between excitatory impulses from muscle spindles and inhibitory impulses from Golgi tendon organs and that this results in a localized muscle cramp.

In other words, muscles tend to cramp specifically when they are overworked and fatigued due to electrical misfiring. One big factor that does appear to support the neuromuscular theory is that stopping and stretching the affected muscles is a pretty universally effective method to fix a cramp when it is actually happening.

What stretching does is put the muscle under tension, invoking afferent activity from the Golgi Tendon Organs part of the muscle responsible for telling it to relax and causing the cramp to dissipate. This would explain why cramps have sometimes been shown to be relieved almost instantly when pickle juice is ingested the nerve stimulation happens almost instantly, whereas the sodium in it takes several minutes to travel to the gut and to be absorbed into the blood.

Because it seems highly likely that fatigue is also implicated in muscle cramping during exercise, finding ways to minimize this is also logical. This is definitely a good idea if your cramps tend to occur during or after periods of heavy sweating, in hot weather, later on during longer activities, or if you generally eat a low sodium or low carb diet.

One note of caution: if you do take on additional sodium, especially in the form of electrolyte drinks, make sure they are strong enough to make a real difference. Most sports drinks are extremely light on electrolytes despite the claims they make on their labels , containing only about to mg sodium per liter 32oz.

Human sweat, on average, comes in at over mg of sodium per liter 32oz , and at Precision Hydration, we often measure athletes losing over 1,mg per liter including myself through our Advanced Sweat Test. This injury may cause deconditioning, pain, and an inability to tolerate the same exercise intensities and durations as before the injury.

Consequently, these risk factors coalesce, alter neuromuscular control, and elicit EAMCs. Multifactorial theory for pathogenesis of exercise-associated muscle cramps EAMCs. Dashed arrows used to help with clarity of understanding the hot, humid, or both environmental conditions and repetitive muscle exercise pathways.

Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Exercise-associated muscle cramps. In: Adams WM, Jardine JF, eds.

Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide. Springer; — This model also proposes that a factor threshold must be reached before EAMCs occur and that this threshold may be positively or negatively mitigated by other risk factors.

Therefore, when predisposed individuals with intrinsic risk factors are exposed to extrinsic factors and exceed their factor threshold, EAMCs occur. This multifactorial theory and factor threshold may explain why EAMCs occur in some individuals and some situations but not others.

Further examination is needed to clarify which factors contribute to EAMCs, how these factors coalesce, and whether some factors are more or less important to EAMC development. Exercise-associated muscle cramps normally occur acutely during or after exercise.

The diagnosis of EAMCs is based on a thorough clinical examination and history. Cramping muscles appear rigid, with the joint often locked in its end range of motion. Clinicians observe visible and palpable knotting or tautness, a key sign differentiating EAMCs from exertional sickling cramps. Fasciculations that wander over the muscle are also possible.

Clinicians should develop treatment protocols for acute EAMCs. Ideally, the treatment approach is individualized Figure 2 and Table 3 and EAMC treatments are continued for up to 1 hour because susceptibility to EAMCs remains high even after cessation. Although most patients can finish exercising after mild EAMCs, some athletes cannot complete their competitions because of EAMCs.

Similarly, pain-relieving agents eg, cryotherapy, massage, electrical stimulation may provide relief from the EAMCs by interrupting the pain-spasm-pain cycle.

The fastest, safest, and most effective treatment for an active EAMC is self-administered or clinician-administered gentle stretching. Athletes can drink water or carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages ad libitum during EAMC treatment if tolerated because these liquids both restore plasma volume and osmolality over time and rehydrate effectively.

Ingesting such large volumes of hypotonic fluids will dilute the blood and could result in life-threatening hyponatremia. Dangerous Volumes of Some Popular Sports Drinks an Athlete With EAMCs Would Need to Ingest to Completely Replace Sweat Sodium and Potassium Losses During Exercise a.

In most situations, rehydration should be oral due to its simplicity, accessibility, and myriad of delivery options eg, cup, water bottle, prepacked container. Intravenous IV fluids are popular among professional athletes, yet they must be administered by a trained person and pose certain risks eg, infection, air embolism, arterial puncture.

Interestingly, perceptual measures eg, thirst, thermal sensation, and rating of perceived exertion are often lower with oral rehydration because IV fluid delivery bypasses fluid volume receptors in the mouth ie, baroreceptors.

Transient receptor potential TRP receptors detect temperature and sensations in the mouth, oropharynx, esophagus, and stomach. Ingredients such as vinegar, cinnamon, capsaicin, and ginger activate these receptors and, in theory, may affect neural function if potent enough.

Conversely, only anecdotal evidence exists regarding mustard's efficacy in relieving acute EAMCs. Authors of other studies assessed the effect of spicy, capsaicin-based TRP agonists on cramp susceptibility.

While the researchers in 1 study 42 reported longer times before cramping, higher contraction forces necessary to induce cramping, and lower muscle activity during cramping, all participants still cramped after ingesting the TRP-agonist drink. Conversely, Behringer et al 41 noted insignificant changes in cramp susceptibility, perceived muscle pain, cramp intensity, and maximal isometric force from 15 minutes to 24 hours postingestion of a TRP agonist.

Further work is needed on TRP agonists and EAMCs. The ingestion of TRP agonists is usually benign, even though gastrointestinal tolerance varies considerably.

Potassium is generally not considered an electrolyte of interest in EAMCs, yet bananas are sometimes used during treatment due to their high potassium and glucose content.

However, no evidence exists on their efficacy. Some data suggested they are unlikely to help by increasing blood potassium; dehydrated participants who ingested 1 or 2 servings of bananas postexercise did not experience increases in plasma potassium concentrations or plasma volume until 60 minutes after consumption.

If poor nutrition is suspected as a risk factor for an athlete's EAMCs, we advise clinicians to advocate for a well-rounded pre-exercise nutrition plan and consult with a registered dietitian before implementing dietary interventions. Quinine and quinine products eg, tonic water were once a popular treatment for cramping.

Interestingly, cramp duration, which is the variable of interest in the acute treatment of EAMCs, was not reduced. Importantly, minor and major adverse events were reported in many of the trials eg, gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia.

The first step in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient presenting with recurrent EAMCs is a thorough medical evaluation to rule out any intrinsic risk factors, including a history of injury, past EAMC history, chronic medical conditions, medication use, or allergies Figure 2 and Table 3.

After ruling out underlying conditions, the clinician should thoroughly question the patient to determine if pertinent extrinsic or intrinsic risk factors exist.

Risk factors consistently associated with EAMCs include pain, 21 a history or previous occurrence of EAMCs, 21 , 22 , 48 muscle damage or injury, 18 , 21 , 31 , 48 prolonged exercise durations, 1 , 20 , 30 , 48 and faster finishing times than anticipated.

The strongest and most recent evidence 4 , 9 suggested that EAMCs are due to changes in the neuromuscular system, yet most diagnostic questions revolve around factors that affect nervous system excitability Table 3.

These questions can be asked before and after each EAMC to help clinicians identify consistent risk factors. Targeted prevention strategies for those risk factors can then be attempted.

Many EAMC prevention recommendations have been advocated, but unfortunately, most either lack support from strong patient-oriented studies or are based on anecdotes Table 2. Indeed, much of the published EAMC prevention advice is derived from studies of electrically induced cramps rather than EAMCs, is anecdotal, is often too generic eg, consume more salt , or fails to account for the complexity of EAMC pathogenesis.

Moreover, many patients and clinicians lack an understanding of the possible causes and risk factors for EAMCs and are overly confident about the contributions of hydration and electrolytes to EAMCs. Sport drink consumption and electrolyte supplementation are frequently touted as effective for preventing EAMCs, though the content of sports drinks and electrolyte supplementation products varies greatly Table 4.

However, in the s, investigators 11 observed that workers prevented EAMCs by consuming saline or adding salt to their beverages. However, in both studies, 53 , 54 the athletes still experienced cramping, and the experimental designs prohibited identification of the ingredient responsible for this effect because the drink contained multiple ingredients eg, electrolytes and carbohydrates.

Still, the large carbohydrate load Clinicians should be wary of sport drinks that contain stimulants eg, caffeine , which may cause an increase in nervous system excitability and, theoretically, predispose patients to EAMCs.

Conversely, the authors 1 , 18 , 20 , 22 of several studies failed to show differences in plasma electrolyte concentrations in athletes with and those without EAMCs.

Sodium supplementation did not differ between ultramarathoners with and those without EAMCs. If clinicians suspect hydration is a risk factor for recurrent EAMCs, we recommend sweat testing. Determining the sweat rate is relatively simple and only requires body weight to be measured before and after exercise.

Clinicians must also know the duration of exercise and the volume or weight of any fluids ingested or lost ie, urination. Nonetheless, sweat electrolyte estimates are available for many sports. Combining sweat test results with a well-balanced, nutritious diet that considers the athlete's unique carbohydrate, fluid, and electrolyte needs will better ensure that he or she is prepared for exercise and minimize the risk of hyponatremia.

Some clinicians use IV fluids to prevent EAMCs and believe they are effective. Although static stretching effectively treats EAMCs, 5 , 22 , 35 it appears to be ineffective as a prophylactic strategy. In a laboratory study, 56 three 1-minute bouts of static or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation hold-relax with agonist contraction stretching did not lower cramp susceptibility.

In observational studies of athletes, investigators 21 , 22 , 30 also consistently failed to demonstrate relationships among flexibility, range of motion, and stretching frequency, duration, or timing and EAMC occurrence. Moreover, Golgi tendon organ inhibition was unaffected by a single bout of clinician-applied static stretching to the triceps surae both immediately and up to 30 minutes poststretching.

Neuromuscular retraining with exercise shows promise for EAMC prevention. Wagner et al 3 found that a triathlete's hamstrings EAMCs were eliminated by lowering hamstrings activity during running and improving gluteal strength and endurance. To achieve this outcome, the patient required few professional visits once a month for 8 months and just a short minute daily at-home protocol.

Fatigue is hypothesized to be a main factor in EAMC development and overexertion is often tied to EAMCs, 9 so it is vital to ensure that athletes exercise with appropriate work-to-rest ratios. Advances in our understanding of EAMC pathogenesis have emerged in the last years and suggested that alterations in neuromuscular excitability and, to a much lesser extent, dehydration and electrolyte losses are the predominant factors in their pathogenesis.

Strong evidence supports EAMC treatments that include exercise cessation rest and gentle stretching until abatement, followed by techniques to address the underlying precipitating factors.

However, little patient-oriented evidence exists regarding the best methods for EAMC prevention. Therefore, rather than providing generalized advice, we recommend clinicians take a multifaceted and targeted approach that incorporates an individual's unique EAMC risk factors when trying to prevent EAMCs.

Recipient s will receive an email with a link to 'An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps' and will not need an account to access the content. Subject: An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps.

Sign In or Create an Account. Search Dropdown Menu. header search search input Search input auto suggest. User Tools Dropdown. Sign In. Toggle Menu Menu Home JAT ATEJ NATA Journals Page NATA. org About Mission Statement JAT Editors and Editorial Board JAT Pub Med Central JAT CEU Quiz Issues Present Archive Archive Online First For Authors Help.

Skip Nav Destination Close navigation menu Article navigation. Volume 57, Issue 1. Previous Article Next Article. ACUTE EAMC DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT. for over 14 years. Let us help you get back in the game!

Body weight Exercises with Physical Therapist, Jason and Physician Assistant, Eileen! Banded Hip Exercises with Physical Therapist, Melissa!

Stability Lunges Multidirectional Lunge. Runners Fab 5 Exercises with Physical Therapist, Greg! Turkish Get-Up Challenge with Physical Therapist, John! Squat Optimization with Athletic Trainer, Jason! How We Treat Physical Therapy Dry Needling Aquatic Therapy Massage Therapy Athletic Training Wellness.

Sports Performance Programs Bone Health Program. Close Patient Portal. About Why VTFC Our Team Our Facility Careers at VTFC. Insights Our Blog Video Library. Contact Us Contact Form Medical Record Requests.

I have Exercise-induced cramps strong personal interest in learning how to avoid Exercise-induuced cramping Exercise-induced cramps exercise because I Exercise-inducex to be a Exercise-inducsd sufferer of Exercise Associated Muscle Cramping EAMC back Exercise-incuced I Essential oils for depression competing. As a result, they have Hydrating student athletes widely studied, Eercise-induced no one crmaps knows Exercise-inducer full Cardiovascular exercises for muscle toning about why they occur. Despite this, over the past decade, I seem to have largely managed my issues with cramps by modifying my behavior, diet and expectations of my body. I did this over time through education and experimentation. This theory speculates that a significant disturbance in fluid or electrolyte balance, usually due to a reduction in total body exchangeable sodium stores, causes a contraction of the interstitial fluid compartment around muscles and a misfiring of nerve impulses, leading to cramps. One example is a classic study on salt depletion that was carried out by a pioneering doctor—R. Exercise-associated muscle cramps EAMC are defined as Exercise-induced cramps painful muscle spasms during or immediately following exercise. Cardiovascular exercises for muscle toning are a Exercise-inducrd Exercise-induced cramps Stationery and office supplies occurs Exegcise-induced or after exercise, often during endurance events such as a triathlon or marathon. Elite athletes experience cramping due to paces at higher intensities. It is widely believed that excessive sweating due to strenuous exercise can lead to muscle cramps. Deficiency of sodium and other electrolytes may lead to contracted interstitial fluid compartments, which may exacerbate the muscle cramping.

Exercise-induced cramps -

for over 14 years. Let us help you get back in the game! Body weight Exercises with Physical Therapist, Jason and Physician Assistant, Eileen! Banded Hip Exercises with Physical Therapist, Melissa!

Stability Lunges Multidirectional Lunge. Runners Fab 5 Exercises with Physical Therapist, Greg! Turkish Get-Up Challenge with Physical Therapist, John!

Squat Optimization with Athletic Trainer, Jason! How We Treat Physical Therapy Dry Needling Aquatic Therapy Massage Therapy Athletic Training Wellness.

Sports Performance Programs Bone Health Program. Close Patient Portal. About Why VTFC Our Team Our Facility Careers at VTFC. Insights Our Blog Video Library.

Contact Us Contact Form Medical Record Requests. When first proposed, the theory emphasized the importance of fatigue-induced alterations in afferent activity, resulting in overexcitation at the α motor neuron. However, it is unclear how fatigue alters this signaling: if a fatigue threshold must be reached before patients experience EAMCs, or whether fatigue-induced changes in excitability can be modulated by other factors.

What is known is that well-trained and conditioned athletes still develop EAMCs. Also, training history does not always predict EAMC occurrence. Contrary to the theory, in 1 laboratory study, researchers 32 noted that localized, fatiguing contractions decreased electrically induced cramp susceptibility.

Lastly, authors of many of the laboratory studies 17 , 24 — 27 that supported this theory used low-frequency electrical stimulation to induce cramps.

This technique allows cramp susceptibility in different muscles 33 to be examined and can discriminate between crampers and noncrampers. Thus, questions exist about the applicability of the findings to EAMCs.

Building on the Schwellnus theory, 9 Miller 4 recently proposed an EAMC pathophysiology model focused on how multiple risk factors interact to elicit a chain reaction that alters neuromuscular control and induces EAMCs Figure 1. In this model, 4 he theorized that numerous unique intrinsic and extrinsic factors coalesce through different pathways and elicit EAMCs.

For example, consider an athlete who sustains a muscle injury. This injury may cause deconditioning, pain, and an inability to tolerate the same exercise intensities and durations as before the injury.

Consequently, these risk factors coalesce, alter neuromuscular control, and elicit EAMCs. Multifactorial theory for pathogenesis of exercise-associated muscle cramps EAMCs. Dashed arrows used to help with clarity of understanding the hot, humid, or both environmental conditions and repetitive muscle exercise pathways.

Reprinted by permission from Miller KC. Exercise-associated muscle cramps. In: Adams WM, Jardine JF, eds. Exertional Heat Illness: A Clinical and Evidence-Based Guide.

Springer; — This model also proposes that a factor threshold must be reached before EAMCs occur and that this threshold may be positively or negatively mitigated by other risk factors. Therefore, when predisposed individuals with intrinsic risk factors are exposed to extrinsic factors and exceed their factor threshold, EAMCs occur.

This multifactorial theory and factor threshold may explain why EAMCs occur in some individuals and some situations but not others. Further examination is needed to clarify which factors contribute to EAMCs, how these factors coalesce, and whether some factors are more or less important to EAMC development.

Exercise-associated muscle cramps normally occur acutely during or after exercise. The diagnosis of EAMCs is based on a thorough clinical examination and history. Cramping muscles appear rigid, with the joint often locked in its end range of motion.

Clinicians observe visible and palpable knotting or tautness, a key sign differentiating EAMCs from exertional sickling cramps. Fasciculations that wander over the muscle are also possible. Clinicians should develop treatment protocols for acute EAMCs. Ideally, the treatment approach is individualized Figure 2 and Table 3 and EAMC treatments are continued for up to 1 hour because susceptibility to EAMCs remains high even after cessation.

Although most patients can finish exercising after mild EAMCs, some athletes cannot complete their competitions because of EAMCs. Similarly, pain-relieving agents eg, cryotherapy, massage, electrical stimulation may provide relief from the EAMCs by interrupting the pain-spasm-pain cycle.

The fastest, safest, and most effective treatment for an active EAMC is self-administered or clinician-administered gentle stretching.

Athletes can drink water or carbohydrate-electrolyte beverages ad libitum during EAMC treatment if tolerated because these liquids both restore plasma volume and osmolality over time and rehydrate effectively. Ingesting such large volumes of hypotonic fluids will dilute the blood and could result in life-threatening hyponatremia.

Dangerous Volumes of Some Popular Sports Drinks an Athlete With EAMCs Would Need to Ingest to Completely Replace Sweat Sodium and Potassium Losses During Exercise a. In most situations, rehydration should be oral due to its simplicity, accessibility, and myriad of delivery options eg, cup, water bottle, prepacked container.

Intravenous IV fluids are popular among professional athletes, yet they must be administered by a trained person and pose certain risks eg, infection, air embolism, arterial puncture.

Interestingly, perceptual measures eg, thirst, thermal sensation, and rating of perceived exertion are often lower with oral rehydration because IV fluid delivery bypasses fluid volume receptors in the mouth ie, baroreceptors. Transient receptor potential TRP receptors detect temperature and sensations in the mouth, oropharynx, esophagus, and stomach.

Ingredients such as vinegar, cinnamon, capsaicin, and ginger activate these receptors and, in theory, may affect neural function if potent enough.

Conversely, only anecdotal evidence exists regarding mustard's efficacy in relieving acute EAMCs. Authors of other studies assessed the effect of spicy, capsaicin-based TRP agonists on cramp susceptibility.

While the researchers in 1 study 42 reported longer times before cramping, higher contraction forces necessary to induce cramping, and lower muscle activity during cramping, all participants still cramped after ingesting the TRP-agonist drink.

Conversely, Behringer et al 41 noted insignificant changes in cramp susceptibility, perceived muscle pain, cramp intensity, and maximal isometric force from 15 minutes to 24 hours postingestion of a TRP agonist. Further work is needed on TRP agonists and EAMCs. The ingestion of TRP agonists is usually benign, even though gastrointestinal tolerance varies considerably.

Potassium is generally not considered an electrolyte of interest in EAMCs, yet bananas are sometimes used during treatment due to their high potassium and glucose content. However, no evidence exists on their efficacy.

Some data suggested they are unlikely to help by increasing blood potassium; dehydrated participants who ingested 1 or 2 servings of bananas postexercise did not experience increases in plasma potassium concentrations or plasma volume until 60 minutes after consumption.

If poor nutrition is suspected as a risk factor for an athlete's EAMCs, we advise clinicians to advocate for a well-rounded pre-exercise nutrition plan and consult with a registered dietitian before implementing dietary interventions.

Quinine and quinine products eg, tonic water were once a popular treatment for cramping. Interestingly, cramp duration, which is the variable of interest in the acute treatment of EAMCs, was not reduced.

Importantly, minor and major adverse events were reported in many of the trials eg, gastrointestinal distress, thrombocytopenia.

The first step in the diagnosis and treatment of a patient presenting with recurrent EAMCs is a thorough medical evaluation to rule out any intrinsic risk factors, including a history of injury, past EAMC history, chronic medical conditions, medication use, or allergies Figure 2 and Table 3.

After ruling out underlying conditions, the clinician should thoroughly question the patient to determine if pertinent extrinsic or intrinsic risk factors exist. Risk factors consistently associated with EAMCs include pain, 21 a history or previous occurrence of EAMCs, 21 , 22 , 48 muscle damage or injury, 18 , 21 , 31 , 48 prolonged exercise durations, 1 , 20 , 30 , 48 and faster finishing times than anticipated.

The strongest and most recent evidence 4 , 9 suggested that EAMCs are due to changes in the neuromuscular system, yet most diagnostic questions revolve around factors that affect nervous system excitability Table 3. These questions can be asked before and after each EAMC to help clinicians identify consistent risk factors.

Targeted prevention strategies for those risk factors can then be attempted. Many EAMC prevention recommendations have been advocated, but unfortunately, most either lack support from strong patient-oriented studies or are based on anecdotes Table 2.

Indeed, much of the published EAMC prevention advice is derived from studies of electrically induced cramps rather than EAMCs, is anecdotal, is often too generic eg, consume more salt , or fails to account for the complexity of EAMC pathogenesis.

Moreover, many patients and clinicians lack an understanding of the possible causes and risk factors for EAMCs and are overly confident about the contributions of hydration and electrolytes to EAMCs.

Sport drink consumption and electrolyte supplementation are frequently touted as effective for preventing EAMCs, though the content of sports drinks and electrolyte supplementation products varies greatly Table 4. However, in the s, investigators 11 observed that workers prevented EAMCs by consuming saline or adding salt to their beverages.

However, in both studies, 53 , 54 the athletes still experienced cramping, and the experimental designs prohibited identification of the ingredient responsible for this effect because the drink contained multiple ingredients eg, electrolytes and carbohydrates. Still, the large carbohydrate load Clinicians should be wary of sport drinks that contain stimulants eg, caffeine , which may cause an increase in nervous system excitability and, theoretically, predispose patients to EAMCs.

Conversely, the authors 1 , 18 , 20 , 22 of several studies failed to show differences in plasma electrolyte concentrations in athletes with and those without EAMCs. Sodium supplementation did not differ between ultramarathoners with and those without EAMCs.

If clinicians suspect hydration is a risk factor for recurrent EAMCs, we recommend sweat testing. Determining the sweat rate is relatively simple and only requires body weight to be measured before and after exercise.

Clinicians must also know the duration of exercise and the volume or weight of any fluids ingested or lost ie, urination. Nonetheless, sweat electrolyte estimates are available for many sports. Combining sweat test results with a well-balanced, nutritious diet that considers the athlete's unique carbohydrate, fluid, and electrolyte needs will better ensure that he or she is prepared for exercise and minimize the risk of hyponatremia.

Some clinicians use IV fluids to prevent EAMCs and believe they are effective. Although static stretching effectively treats EAMCs, 5 , 22 , 35 it appears to be ineffective as a prophylactic strategy. In a laboratory study, 56 three 1-minute bouts of static or proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation hold-relax with agonist contraction stretching did not lower cramp susceptibility.

In observational studies of athletes, investigators 21 , 22 , 30 also consistently failed to demonstrate relationships among flexibility, range of motion, and stretching frequency, duration, or timing and EAMC occurrence.

Moreover, Golgi tendon organ inhibition was unaffected by a single bout of clinician-applied static stretching to the triceps surae both immediately and up to 30 minutes poststretching.

Neuromuscular retraining with exercise shows promise for EAMC prevention. Wagner et al 3 found that a triathlete's hamstrings EAMCs were eliminated by lowering hamstrings activity during running and improving gluteal strength and endurance.

To achieve this outcome, the patient required few professional visits once a month for 8 months and just a short minute daily at-home protocol.

Fatigue is hypothesized to be a main factor in EAMC development and overexertion is often tied to EAMCs, 9 so it is vital to ensure that athletes exercise with appropriate work-to-rest ratios.

Advances in our understanding of EAMC pathogenesis have emerged in the last years and suggested that alterations in neuromuscular excitability and, to a much lesser extent, dehydration and electrolyte losses are the predominant factors in their pathogenesis.

Strong evidence supports EAMC treatments that include exercise cessation rest and gentle stretching until abatement, followed by techniques to address the underlying precipitating factors.

However, little patient-oriented evidence exists regarding the best methods for EAMC prevention. Therefore, rather than providing generalized advice, we recommend clinicians take a multifaceted and targeted approach that incorporates an individual's unique EAMC risk factors when trying to prevent EAMCs.

Recipient s will receive an email with a link to 'An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps' and will not need an account to access the content.

Subject: An Evidence-Based Review of the Pathophysiology, Treatment, and Prevention of Exercise-Associated Muscle Cramps. The physicians are all experienced runners and board certified sports medicine physicians.

They treat all physically active people with a special focus on the endurance athlete. The best way to prevent severe muscle cramps is to stay well hydrated before, during and after exercise.

This is especially important in the hot summer months. Stretching your legs before and after can also help. These cramps often occur in the legs or feet. Stay well hydrated, do some light stretching and contact your doctor if the cramps start to become more frequent or severe.

I am 84 years old and I ;have severe cramping at night. especially after heavy labor during the day. There must be some specific solutions beyond the general statements I see here! I had cramping almost daily for years until I read on the internet that it might be a magnesium deficiency.

I started taking magnesium supplements and the cramps went away. I often would get leg cramps due to standing on cement floors to do my job. One night they were so severe I was outside trying to walk them off when my neighbour,who happened to be of Indian descent,advised me to put on a pair of socks and put wine cork in the socks,which she supplied.

Amazingly the cramp was gone within seconds. I have since advised many people to do this,with excellent results.

Muscle building after Nov 21, when you have a Exercise-induced cramps Exercise-inducerbut research has found that Cardiovascular exercises for muscle toning are mostly not to carmps for the cramps we get during or after exercise. Buskard recently published an article in the Strength and Conditioning Journal in which he reviewed all the available research on this topic. Factors that we traditionally blamed for muscle cramps during exercise include:. Accumulation of waste products that interfere with the muscle contraction.

Mir scheint es der ausgezeichnete Gedanke